BIODIVERSITY OF CELLULOLYTIC BACTERIA IN SOIL COLLECTED FROM SOME WOOD PROCESSING AREAS IN VIETNAM

Department of Biotechnology, Joint Vietnam - Russia Tropical Science and Technology Research Center

63 Nguyen Van Huyen, Nghia Do, Hanoi, Vietnam

Số điện thoại: +84 986109694; Email: hongdt1009@gmail.com

Nội dung chính của bài viết

Tóm tắt (Abstract)

Cellulose-degrading microorganisms play an important role in the decomposition of organic matter and have potential applications in biotechnology and environmental remediation. In this study, nine soil samples were collected from wood-processing areas in three different regions of Vietnam (three samples per region): the North (Lao Cai province), the Central region (Thanh Hoa province), and the South (Dong Nai province). A total of 28 bacterial strains with CMC-degrading activity were successfully isolated from these soil samples, with the northern region yielding the highest number of isolates (12 strains). All 28 isolates were then evaluated for their morphological, which allowed classification into seven distinct morphological groups. Based on the CMC degradation ability, five strains (D183.1.B1, D111.1.B1, D183.2.B3, D751.1.B2 and D111.3.B2) exhibiting the highest cellulolytic activity (respectively: 24.33 ± 0.33; 23.0 ± 0.58; 21.33 ± 0.33; 21.33 ± 0.67; 18.33 ± 0.33) were selected for further characterization. 16S rRNA gene sequencing results identified these five strains as: Bacillus velezensis D183.1.B1, Bacilus amyloliquefaciens D183.2.B3, Bacillus cellulosilyticus D111.1.B1, Pseudomonas aeruginosa D111.3. B2, Pseudomonas fluorescens D751.1.B2. The effects of pH, temperature, and incubation time on cellulase enzyme production were also investigated. The results indicated that pH 6–8, temperature around 35 °C, and culture time of 48–72 hours yielded the highest cellulase activities, ranging from 1.7 to 7.8 U/mL. These findings enhance the understanding of the diversity and enzymatic potential of cellulose-degrading bacteria inhabiting wood-processing environments in Vietnam and provide a scientific basis for their application in biomass decomposition and sustainable wastewater management.

Từ khóa (Keywords)

Bacillus, biodiversity, cellulose-degrading bacteria, cellulase enzyme, Pseudomonas

Chi tiết bài viết

Bài báo này được cấp phép theo Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- Highlights:

Collecting soil samples in some wood processing areas in Vietnam.

Isolating cellulose-degrading bacteria from soil samples.

Evaluating some biological characteristics of cellulose-degrading bacterial strains.

1. INTRODUCTION

The wood-processing industry is a key contributor to economic development in many countries, including Vietnam. However, this sector generates large volumes of wastewater rich in recalcitrant organic compounds, notably lignocellulosic materials such as cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin [1]. These compounds are difficult to degrade by conventional wastewater treatment microorganisms, creating significant challenges for environmental management and water pollution control.

Biological treatment using cellulose-degrading microorganisms (cellulolytic bacteria) offers a promising solution for enhancing the breakdown of these complex pollutants. Cellulolytic bacteria produce cellulase enzymes capable of hydrolyzing β-1,4-glycosidic bonds in cellulose, converting it into glucose and simpler sugars that microbial communities can readily metabolize [2]. This enzymatic process accelerates lignocellulose decomposition, lowers chemical oxygen demand (COD), and improves overall wastewater quality.

Recent research has confirmed the feasibility of exploiting cellulose-rich industrial waste streams for both cellulase production and biological treatment. For instance, fiber sludge from pulp and paper mills - a cellulose-rich residue - has been successfully used for bacterial cellulase production without extensive pretreatment, highlighting its potential for bioconversion and enzyme generation [3]. Likewise, bacteria capable of degrading cellulose, starch, and lipids have been isolated directly from pulp and paper wastewater, demonstrating the presence of native microbial populations adapted to cellulose degradation [4]. In addition, wastewater from the wood-based panel industry can exhibit extremely high COD levels (up to ~11,000 mgO₂/L) and contains cellulose degradation products, lignin, and phenolic compounds, underscoring the need for effective biological treatment systems [5].

In Vietnam, several studies have investigated cellulolytic bacteria derived from wood-processing byproducts and related environments. Bacillus strains with strong carboxymethyl-cellulose (CMC) degrading activity were isolated from wood-processing waste in Hung Yen province and Ha Noi city and shown to achieve optimal cellulase production under specific pH, temperature, and incubation conditions [6]. Research on converting cellulose-rich pulp sludge into bacterial cellulose (nanocellulose) further indicates both the high cellulose content of industrial waste streams and the potential for biological valorization [7]. Moreover, Vietnamese wood-processing wastewater frequently contains lignin, dyes, suspended solids, and chemical preservatives, posing environmental risks if left untreated [1].

However, most existing studies in Vietnam have focused on the isolation of cellulolytic bacteria from a limited number of locations or on optimizing enzyme production under laboratory conditions, rather than systematically comparing strains from different ecological and industrial contexts. There is also a lack of comprehensive characterization of the enzymatic potential and environmental adaptability of native strains under conditions representative of real wastewater systems. Furthermore, few studies have explored the connection between the geographical origin of isolates, their cellulolytic efficiency, and potential applicability to region-specific wastewater treatment strategies.

Harnessing native microbial strains adapted to local ecological conditions could improve the efficiency and sustainability of biological treatments for cellulose-rich wood-processing wastewater. Therefore, this study aimed to isolate cellulose-degrading bacteria from soil in some wood processing areas in Vietnam, evaluate their cellulase activity and optimize culture conditions to maximize enzyme production. The results will provide a microbial resource base for future biotechnological applications in biomass decomposition and sustainable wastewater management within the wood industry.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Material

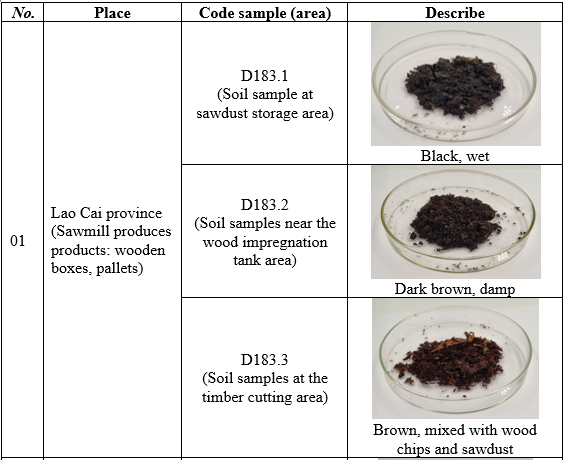

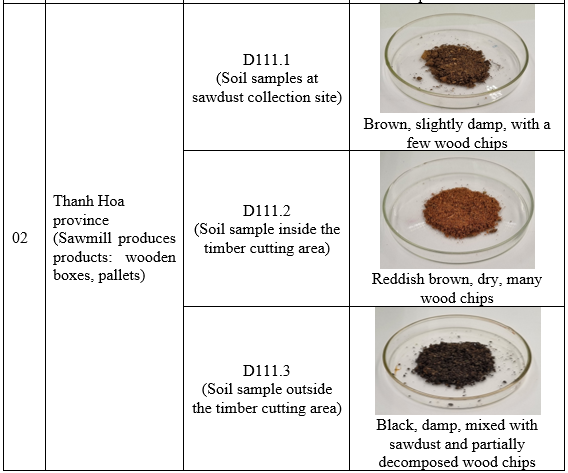

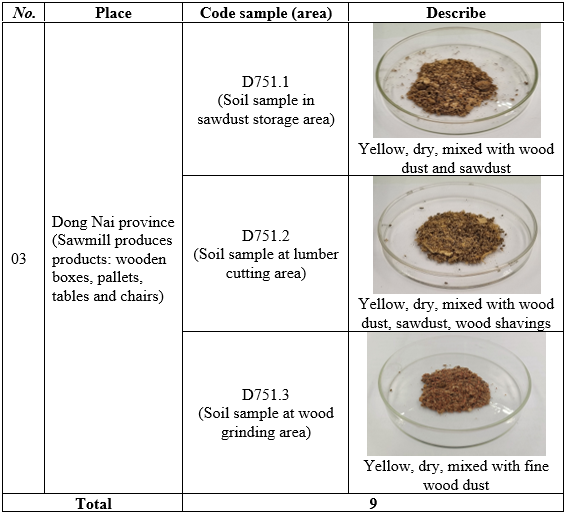

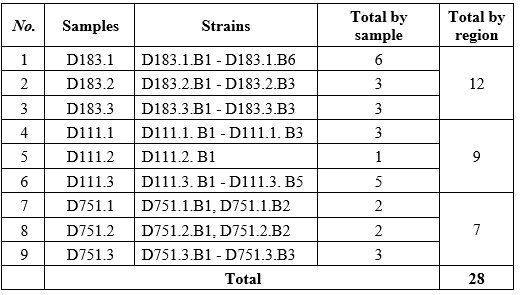

The samples used in the study were listed in Table 1 below.

Table 1. List of samples

2.2. Methods

Sample collection

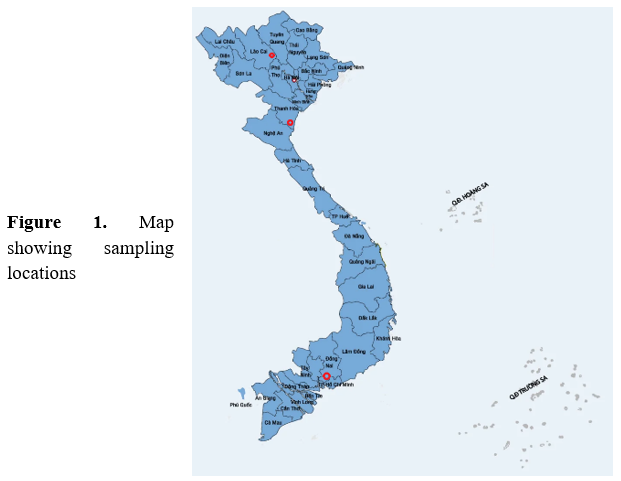

A total of nine surface soil samples were collected from three representative wood-processing regions of Vietnam: the North (Lao Cai), Central (Thanh Hoa), and South (Dong Nai). At each region, three sites adjacent to sawmills or wood-processing facilities were selected based on the visible presence of lignocellulosic residues such as sawdust and wood chips, following the approach described by R. Mahmood et al. (2020) [4]. Soil samples were taken from a depth of 0–10 cm using sterilized stainless-steel spatulas, as microorganisms involved in cellulose degradation are often concentrated in surface layers rich in organic matter [6]. At each site, five subsamples were combined into one composite sample (~500 g). All tools were disinfected with 70% ethanol between collections to avoid cross-contamination. Samples were placed in sterile polyethylene bags, labeled with site codes and immediately stored at 4 °C. The samples were transported to the laboratory and processed under aseptic conditions for bacterial isolation. The collected samples were coded as D183 (North), D111 (Central), and D751 (South).

Isolation of microorganisms from soil samples.

Cellulose-degrading bacteria were isolated from soil samples using the carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) agar plate method described by D. Kungulovski et al. (2023) with minor modifications [8]. Briefly, 1 g of soil sample was serially diluted in sterile distilled water up to 10⁻⁶. Aliquots (0.1 mL) of appropriate dilutions were spread on CMC agar medium (1% CMC, 0.5% peptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.1% K₂HPO₄, 0.05% MgSO₄·7H₂O, 2% agar, pH 7.0) and incubated at 35°C for 48 h. Distinct colonies were purified by repeated streaking on fresh CMC agar plates. All isolates were coded according to sampling sites (e.g., D183.1.B1) and stored in 20% glycerol at –80°C for long-term preservation [3].

Morphological characterization of bacterial colonies and cells.

Colony morphology was examined from pure cultures grown on nutrient agar (NA) plates incubated at 35 ± 1 °C for 48 h. The colonies were observed under uniform lighting and described according to size, shape, color, surface texture, margin, elevation, opacity, and pigment production, following the criteria of A. M. Sousa et al. (2013) [9]. Photographs were taken using a digital camera with a 10 mm scale bar for documentation.

Cell morphology was examined from freshly grown cultures on NA slants. Smears were prepared on clean glass slides, heat-fixed, and stained using the Gram staining method to determine cell wall type, shape, and arrangement (e.g., rods, cocci, chains). Observations were made under a compound light microscope at 1000× magnification (oil immersion). Cell size was measured using a calibrated ocular micrometer.

Screening of cellulolytic activity on CMC agar of bacterial strains.

The cellulolytic potential of the bacterial strains was assessed using an agar well diffusion assay with modifications from the method of D. Kungulovski et al. (2023) [8]. Briefly, a single colony of each isolate was cultured in 5 mL of LB broth for 24 h. After incubation, the culture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm to collect the cell-free supernatant. Aliquots of 10 µL were dispensed into wells (7 mm in diameter) prepared on agar plates containing 1% (w/v) CMC. The plates were incubated at room temperature for 48 h. To visualize hydrolysis, the agar was flooded with 1% Lugol’s iodine solution for 15 min and then rinsed with 1 M NaCl. The formation of clear zones around the wells indicated enzymatic degradation of CMC. The degradation index was calculated according to the formula: A = D – d [10], where A represents the degradation ability (mm), D is the diameter of the hydrolysis zone (mm), and d is the well diameter (mm). Each isolate was tested in triplicate, and cellulase activity was classified following the criteria of Nguyen Thi Thuy Nga et al. (2015) [11]:

A < 10 mm: weak cellulolytic activity

10 mm ≤ A < 15 mm: moderate cellulolytic activity

15 mm ≤ A < 20 mm: fairly strong cellulolytic activity

A ≥ 20 mm: strong cellulolytic activity.

Determination of the effects of pH, temperature, and incubation time on cellulase activity

Five bacterial strains exhibiting the highest CMC-degrading activity were selected for enzyme production studies. Each strain was activated on nutrient agar (NA) at 35 °C for 24 h, then inoculated into liquid CMC medium (g/L: CMC-Na 10, peptone 5, yeast extract 5, K₂HPO₄ 1, MgSO₄.7H₂O 0.5; initial pH varied depending on the test). The inoculum was adjusted to OD₆₀₀ = 0.10 ± 0.01, corresponding to approximately 10⁷–10⁸ CFU/mL. All experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3).

(i) Effect of pH.

The influence of pH on cellulase production was studied using media buffered at pH 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9. Buffers included citrate–phosphate (pH 5–6), phosphate (pH 7), and Tris–HCl (pH 8–9), each at 50 mM. Cultures were incubated in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 50 mL working volume at 35 °C, 150 rpm for 48 h [12]. The culture supernatant obtained after centrifugation at 8,000 ×g for 10 min was used as crude enzyme extract.

(ii) Effect of temperature.

To determine the optimal temperature, cultures were incubated at 15, 30, 35, 40, and 50 °C for 48 h in CMC medium at pH 7.0. The cellulase activity of each crude extract was then determined as described below [13].

(iii) Effect of incubation time.

The effect of incubation time was evaluated by sampling at 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 h under optimal pH and temperature conditions (pH 7.0, 35 °C). Samples (5 mL) were withdrawn at each time point, centrifuged, and the supernatants were analyzed for cellulase activity.

(iv) Determination of cellulase activity (DNS method).

Cellulase activity was assayed using the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) method with 1% (w/v) CMC as substrate [14]. The reaction mixture (0.5 mL crude enzyme + 0.5 mL substrate) was incubated for 30 min under the respective test condition, then terminated by adding 1 mL DNS reagent and boiling for 5 min. After cooling, the mixture was diluted to 10 mL with distilled water, and absorbance was measured at 540 nm. Reducing sugar released was calculated using a glucose standard curve (20–500 µg/mL). One unit (U) of cellulase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme releasing 1 µmol of glucose equivalent per minute under assay conditions [15].

PCR amplification and sequencing of 16S rRNA Gene: The 16S rRNA gene of bacterial isolates was amplified using the universal primer pair 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGCCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-TACGGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′). The PCR reaction mixture (25 µL) included 12.5 µL of 2× PCR Master Mix, 1 µL of each primer (10 µM), 1 µL of template DNA, and nuclease-free water. Thermocycling was performed with the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min; 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 55°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 90 s; and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min [16]. Amplification products were confirmed via 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis stained with ethidium bromide. Target bands were purified using a commercial gel extraction kit according to the manufacturer's instructions and submitted for Sanger sequencing.

Sequence analysis: The sequencing results were compared to related data in Genbank by the BLAST search on NCBI.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± standard error (SE) of three replicates. The results were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, and significant differences among means were evaluated using Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05). The condition giving the highest enzyme activity was considered optimal.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Isolation of cellulose-degrading bacteria

A total of 28 bacterial strains with CMC degrading activity were isolated from nine soil samples collected in three representative wood-processing regions of Vietnam: the northern (Lao Cai), the central (Thanh Hoa) and the southern (Dong Nai). The distribution of isolates differed across regions: the Northern region yielded the highest number of strains (12 strains, 42.9%), followed by the Central (9 strains, 32.1%) and Southern (7 strains, 25.0%).

Table 2. Statistics of results of isolating bacteria with CMC degrading activity

The successful isolation of 28 CMC-degrading bacterial strains from nine soil samples collected in three representative wood-processing regions of Vietnam highlights both the rich microbial diversity and the influence of regional environmental factors on cellulolytic populations (Table 2).

Several ecological factors may explain the higher isolation frequency in the North. Lao Cai province experiences a cooler climate (average annual temperature ~20oC), higher annual rainfall, and greater soil humidity (average annual rainfall ~2000 mm) [17], which create stable moisture levels favorable for cellulolytic bacteria that require water to diffuse enzymes and hydrolyze insoluble cellulose. Similar correlations between soil moisture and cellulolytic abundance have been reported in temperate forest soils and pulp-and-paper effluents, where moderate temperatures (20–30 °C) and high organic matter supported diverse cellulose degraders [4]. In Vietnam, D. T. T. Tam et al. (2023) likewise found that Bacillus strains isolated from northern wood-processing wastes were more numerous and enzymatically active than those from drier southern sites [6].

In contrast, Thanh Hoa province and Dong Nai province, representing the Central and Southern regions, experience higher mean annual temperatures and longer dry seasons, conditions that can limit the persistence of moisture-dependent cellulolytic populations and reduce the recovery of culturable strains. Seasonal drying may also reduce the availability of fresh lignocellulosic residues, further constraining microbial diversity. Comparable north - south gradients in cellulolytic diversity have been documented in China’s subtropical - tropical transition zones [3], supporting the notion that climatic factors, particularly soil moisture and temperature regimes, exert strong controls on the structure of cellulose-degrading communities.

Beyond climate, wood-processing practices differ among the three regions. Samples in the Lao Cai province store larger volumes of sawdust and timber under shaded, humid conditions, likely providing continuous cellulose input and stable microhabitats that sustain dense cellulolytic populations. Conversely, sawdust samples handling in Dong Nai province often occurs in open yards with higher solar exposure, causing desiccation that limits bacterial survival.

Collectively, these results demonstrate that the northern wood-processing soils act as a natural reservoir of cellulolytic bacteria, offering a promising source of strains for biotechnological applications. They also emphasize the importance of targeted sampling strategies that account for climatic and operational differences when prospecting for high-performance cellulose degraders.

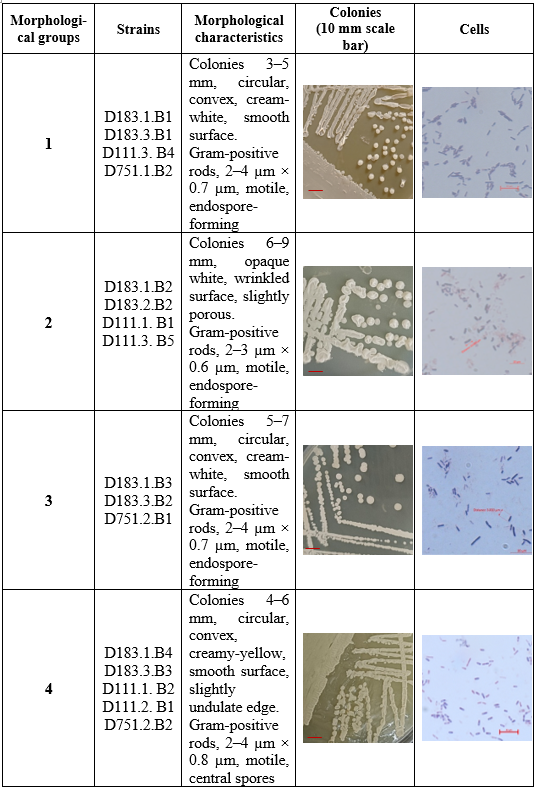

3.2. Morphological and physiological characteristics

Based on colony appearance, 28 strains were classified into seven morphotypes. Microscopy showed most were Gram-positive, rod-shaped, spore-forming, while a minority were Gram-negative rods (Table 3).

Table 3. Morphological grouping of isolated strains

The colony and cellular characteristics of the seven morphological groups show a clear separation between Gram-positive Bacillus-like strains (Groups 1–5) and Gram-negative Pseudomonas-like strains (Groups 6–7). Groups 1–5 exhibit thick-walled, endospore-forming rods and colonies ranging from smooth convex (Groups 1 and 3) to dry and irregular (Group 5). Such variability in colony texture and size - from the wrinkled, opaque Group 2 colonies (6 - 9 mm) to the small, dry Group 5 colonies (1–2 mm) -suggests physiological diversity within Bacillus, which is consistent with previous reports that Bacillus species display wide phenotypic plasticity depending on nutrient levels and cellulose availability [3, 6].

In contrast, Groups 6 and 7 present Gram-negative, non-spore-forming rods with translucent or slightly mucoid colonies, matching typical Pseudomonas traits. Their smooth beige to mucoid colony surfaces and smaller cell size (≈2–3 µm × 0.5 µm) parallel descriptions of cellulose-degrading Pseudomonas isolated from pulp-and-paper wastewater [4] and wood-panel effluents [17]. These genera are well known for versatile carbon metabolism and strong β-glucosidase activity, supporting their role in lignocellulose degradation.

The dominance of Bacillus groups (five of seven) agrees with numerous Vietnamese studies showing Bacillus as the prevalent cellulolytic genus in wood-processing residues because of its ability to secrete high levels of extracellular cellulases and withstand harsh environmental conditions [6]. Similar patterns have been observed internationally, where Bacillus often outcompetes other bacteria in cellulose-rich industrial wastes due to spore formation and enzyme stability [3]. Meanwhile, the presence of Pseudomonas groups, though less frequent, highlights the ecological advantage of mixed microbial consortia; international studies demonstrate thatBacillus - Pseudomonas associations can synergistically enhance lignocellulose degradation [4].

Overall, the morphological data indicate that northern wood-processing soils not only harbor a higher number of isolates but also a broader spectrum of Bacillus morphotypes, while Pseudomonas-like strains occur across regions in smaller numbers. This distribution mirrors global findings that cooler, moister environments favor Bacillus diversity, whereas Pseudomonas maintains a steady presence across varied climates. Such diversity provides a valuable reservoir of native strains for future biological treatment of cellulose-rich wastewater and for industrial enzyme production, reinforcing conclusions drawn from both Vietnamese and international research.

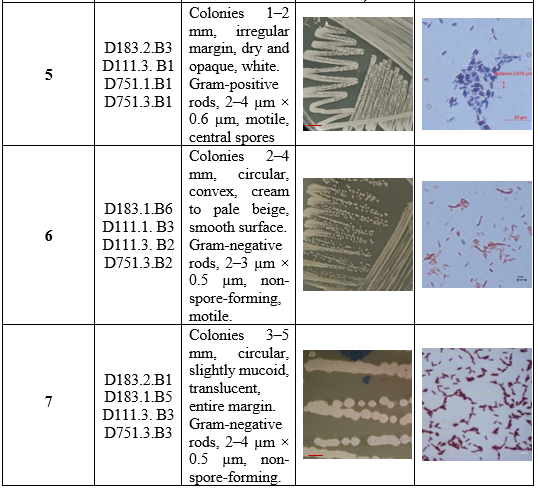

3.3. CMC-degrading activity and screening of high-performing strains

All 28 isolated bacterial strains exhibited CMC-degrading activity ranging from 3.0 ± 0.58 mm (D183.1.B3) to 24.33 ± 0.33 mm (D183.1.B1). Based on halo diameter, the strains were classified into four groups with distinct proportions: weak activity (9 strains, 32.1%), moderate activity (8 strains, 28.6%), fair activity (6 strains, 21.4%), and high activity (5 strains, 17.9%). This distribution highlights that while a considerable fraction of isolates displayed only modest cellulolytic ability, a smaller but significant subset (~18%) showed strong degradation, representing the most promising candidates for applied biotechnology.

Table 4. CMC-degrading activity of isolated strains.

Note: Mean values followed by the same letter indicate no statistically significant difference at the 5% level.

The weak group was characterized by small hydrolysis halos (<10 mm), suggesting low extracellular cellulase production. These isolates are unlikely to have direct industrial value, a finding consistent with previous Vietnamese work where a majority of soil isolates fell below practical thresholds for enzyme applications [10]. The moderate group showed stable cellulase activity (10–15 mm), comparable to reports from D. T. T. Tam et al. (2023), who also noted that such strains can often be improved by optimizing pH, temperature, or substrate conditions [6].

The fair group (15–20 mm) demonstrated clear degradation potential and overlaps with findings by D. Kungulovski et al. (2023), who emphasized that cellulase producers in this range are suitable for small-scale bioassays and pre-treatment trials [8]. Notably, the high activity group (≥20 mm) included five isolates with statistically significant differences from the rest (ANOVA, Tukey HSD). These strains fall within the “strong cellulolytic” category defined by N. T. T. Nga et al. (2015) and parallel the top-performing Bacillus and Pseudomonas isolates reported internationally [11]. For instance, Cavka et al. (2013) observed Bacillus from pulp-mill fiber sludge producing large hydrolysis halos [6], while R. Mahmood et al. (2020) described Pseudomonas isolates from pulp and panel industry effluents with comparable performance [4].

The predominance of Bacillus spp. among the high-activity group in this study is consistent with their known robustness, extracellular enzyme productivity, and spore-forming ability, which confer survival advantages in cellulose-rich, fluctuating environments. The presence of a Pseudomonas isolate in the high-activity group further supports the ecological synergy between Bacillus and Pseudomonas in lignocellulose degradation, as noted by D. Kungulovski et al. (2023) [8].

Taken together, these results confirm both the diversity and ecological specialization of cellulolytic bacteria in Vietnamese wood-processing soils. Although only ~18% of the isolates reached the “high activity” threshold, these strains represent a valuable resource for large-scale cellulase production and biological treatment of lignocellulose-rich effluents, in agreement with both national and international research. Five strains (D183.1.B1, D183.2.B3, D111.1.B1, D111.3. B2, D751.1.B2) with the highest activity with statistically significant differences compared to the remaining strains were selected for further studies.

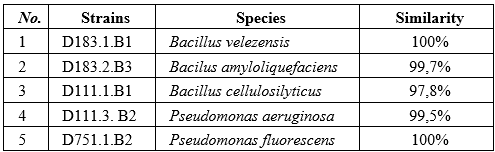

3.4. Phylogenetic identification

The 16S rRNA gene sequencing of the five bacterial strains exhibiting the highest CMC-degrading activity revealed two dominant genera - Bacillus and Pseudomonas - with sequence similarities ranging from 97.8% to 100%. Among them, three isolates (Bacillus velezensis D183.1.B1, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens D183.2.B3, and Bacillus cellulosilyticus D111.1.B1) belonged to the Bacillus subtilis species complex, which is well known for producing large quantities of extracellular enzymes such as cellulases, xylanases, and proteases that play key roles in lignocellulose degradation [3, 8].

Both B. velezensis (100%) and B. amyloliquefaciens (99.7%) demonstrated strong CMC-degrading activities (21 - 24 mm), consistent with previous reports of Bacillus species isolated from soil and wood-processing residues exhibiting potent endo-β-1,4-glucanase and β-glucosidase activities [4, 10]. These results confirm that Bacillus strains, especially members of the B. subtilis complex, are efficient natural cellulase producers capable of thriving under aerobic, neutral-pH conditions common in lignocellulosic environments.

Table 4. Selected bacterial strains and related species on Genbank

The isolate Bacillus cellulosilyticus D111.1.B1 (97.8%) showed a slightly lower similarity than the species-level threshold (98.7%), suggesting that it might represent a closely related variant or potentially a novel strain. B. cellulosilyticus has been described as a cellulolytic species typically found in cellulose-rich ecosystems such as compost and industrial sludge. The detection of a genetically distinct yet enzymatically active strain in this study highlights the possibility of local adaptation among Bacillus populations in Vietnam’s wood-processing soils.

Notably, two isolates from the genus Pseudomonas - Pseudomonas aeruginosa D111.3.B2 (99.5%) and Pseudomonas fluorescens D751.1.B2 (100%) -also displayed strong CMC degradation (halo diameters of 18.33 ± 0.33 mm and 21.33 ± 0.67 mm, respectively). Although Pseudomonas is not traditionally recognized as a dominant cellulolytic genus, several studies have reported its ability to produce endoglucanase, exoglucanase, and β-glucosidase enzymes [18]. P. aeruginosa, in particular, possesses a flexible regulatory network that enables the co-production of multiple hydrolytic enzymes (cellulase–xylanase–esterase complex), thus enhancing cellulose and CMC degradation efficiency.

Compared with previously published Pseudomonas isolates, which typically show cellulase activity corresponding to halo diameters of 10–15 mm [18], the two Pseudomonas strains obtained in this study exhibited remarkably higher enzymatic potential. This suggests that P. aeruginosa D111.3.B2 and P. fluorescens D751.1.B2 may represent rare, naturally occurring cellulolytic variants capable of efficient enzyme secretion and adaptation to cellulose-rich, wood-processing environments in Vietnam.

Overall, both Bacillus and Pseudomonas genera appear to play complementary roles in cellulose degradation. Bacillus contributes a robust extracellular enzymatic system, while Pseudomonas provides metabolic versatility and intermediate degradation capabilities, together generating a synergistic effect in lignocellulose breakdown. The coexistence of these genera in the same ecological niche suggests potential for developing cellulolytic microbial consortia that could be applied in biological pretreatment of industrial wastewater and large-scale cellulase production for sustainable biomass utilization.

3.5. Effect of pH, temperature and culture time on cellulase enzyme activity

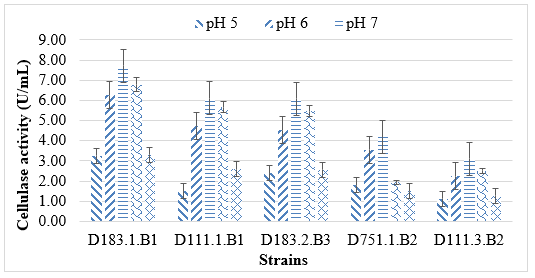

Effect of pH on cellulase enzyme activity.

The cellulase activity of all five selected strains was markedly influenced by the initial pH of the culture medium (Figure 1). In general, enzyme production occurred over a relatively wide pH range (5.0 - 9.0), but the highest cellulase activities were observed under near-neutral conditions (pH 6–8). Among the tested strains, Bacillus velezensis D183.1.B1 showed the strongest enzyme activity, reaching 7.8 U/mL at pH 6, followed closely by B. amyloliquefaciens D183.2.B3 and B. cellulosilyticus D111.1.B1 with maxima around 6.2 - 6.5 U/mL at pH 7. In contrast, the two Pseudomonas isolates (P. fluorescens D751.1.B2 and P. aeruginosa D111.3.B2) exhibited lower enzyme yields (3.0 - 5.0 U/mL) but maintained stable activities across a broader pH range, indicating good adaptability under slightly acidic or alkaline conditions.

These findings are consistent with previous studies showing that cellulase production by Bacillus spp. is typically optimal near neutral pH. For instance, B. subtilis and B. velezensis strains reported by D. Kungulovski et al. (2023) and Cavka et al. (2013) exhibited maximum CMCase activities at pH 6–7, corresponding to the favorable physiological range for enzyme secretion [3, 8]. Similarly, B. amyloliquefaciens strains isolated from lignocellulosic substrates also demonstrated high enzyme productivity under mildly acidic conditions (pH 6.5–7.0), where the enzyme remains structurally stable and resistant to denaturation.

Figure 1. Effect of pH on cellulase enzyme activity of five bacterial strains

The pH response of the Pseudomonas strains aligns with observations from P. fluorescens var. cellulosa [18] and P. aeruginosa [4], which exhibit moderate cellulase activity over pH 6–8. Although Pseudomonas species generally produce lower cellulase levels compared to Bacillus, their ability to maintain activity across variable pH conditions makes them valuable for mixed-culture biodegradation systems. Such robustness suggests their potential to stabilize enzyme efficiency in environments where pH fluctuates, such as wood-processing wastewater or composting systems.

Overall, the results indicate that cellulase biosynthesis by Bacillus strains is pH-dependent and peaks at near-neutral values, while Pseudomonas strains contribute pH tolerance and enzymatic stability. This complementarity supports the hypothesis of a synergistic interaction between Bacillus and Pseudomonas in lignocellulose degradation, where Bacillus ensures high catalytic activity and Pseudomonas enhances resilience under environmental stress. The identified pH range (6–8) therefore represents the optimal condition for large-scale cellulase production and potential application in biological pretreatment of lignocellulosic waste.

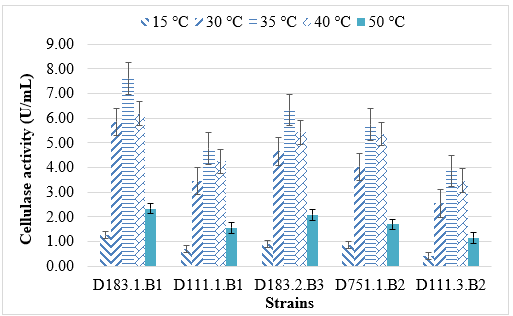

Effect of temperature on cellulase enzyme activity.

The cellulase activity of the five selected bacterial strains (D183.1.B1, D183.2.B3, D751.1.B2, D111.1.B1, and D111.3.B2) varied considerably with temperature, indicating distinct physiological adaptation to environmental conditions. All strains exhibited low enzyme activity at 15 °C, suggesting that cellulase synthesis was significantly reduced at low temperature. Enzyme activity increased sharply between 30 °C and 35 °C, reaching the maximum for all strains at 35 °C, with the highest activity observed in Bacillus velezensis D183.1.B1 (7.6 ± 0.2 U/mL). This demonstrates that moderate temperatures favor both bacterial growth and cellulase expression.

Beyond 40 °C, cellulase activity began to decline in most strains, and a significant decrease was observed at 50 °C. This trend is consistent with the thermal sensitivity of many bacterial cellulases, which tend to denature or lose catalytic efficiency when exposed to higher temperatures. Among the Bacillus strains, B. velezensis D183.1.B1 and B. amyloliquefaciens D183.2.B3 maintained relatively high activity at 40 °C, showing partial thermostability. In contrast, the Pseudomonas strains (D751.1.B2 and D111.3.B2) displayed narrower optimal ranges, consistent with mesophilic enzyme profiles.

Similar findings were reported by Anu et al. (2021), who observed maximal cellulase activity from Bacillus subtilis at 35 - 40 °C [19], and by I. K. Kiio1o et al. (2016), where Bacillus isolates from wood waste produced thermostable cellulases active up to 45 °C [20]. In contrast, Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas aeruginosa typically express cellulases optimally around 30–37 °C [8].

Figure 2. Effect of temperature on cellulase enzyme activity of five bacterial strains

Overall, these results confirm that the isolated Bacillus strains are more thermotolerant and suitable for applications in moderately thermophilic processes such as composting or lignocellulose degradation in wood-processing wastewater. The Pseudomonas strains, although less thermostable, may play important roles in initial cellulose hydrolysis under mesophilic conditions.

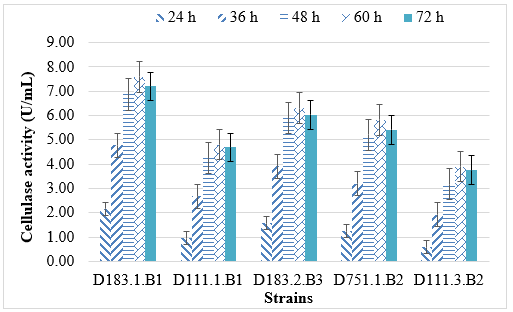

Effect of culture time on cellulase enzyme activity.

The cellulase activity of the five selected bacterial strains showed a distinct trend over the incubation period (24 - 72 h), reflecting the growth dynamics and enzyme secretion patterns typical of Bacillus and Pseudomonas species. In general, cellulase production increased steadily from 24 h to 60 h, reaching its maximum around 48–60 h for most strains, before showing a slight decline at 72 h.

Among the isolates, Bacillus velezensis D183.1.B1 exhibited the highest enzyme activity (7.6 ± 0.2 U/mL at 60 h), followed by B. amyloliquefaciens D183.2.B3 and Pseudomonas fluorescens D751.1.B2. The observed peak coincides with the late exponential to early stationary growth phase, a stage where nutrient availability and metabolic activity support optimal enzyme synthesis. The subsequent decrease at 72 h likely results from nutrient depletion, accumulation of inhibitory metabolites, or feedback repression of enzyme production.

Figure 3. Effect of culture time on cellulase enzyme activity of five bacterial strains

These results are consistent with previous studies. Anu et al. (2021) and S. Singh et al. (2013) reported that Bacillus subtilis and B. amyloliquefaciens strains reached maximal cellulase production between 48 and 72 h, after which enzyme levels declined due to product inhibition [19, 21]. Similarly, Pseudomonas species were found to produce cellulase most effectively within 48–60 h, beyond which enzyme degradation and decreased metabolic activity reduced overall yield [22, 23].

The time-course data confirm that Bacillus strains are generally more efficient and stable producers of cellulase than Pseudomonas strains under the same conditions, highlighting their potential for industrial-scale enzyme production or biological treatment of lignocellulosic waste.

4. CONCLUSION

This study successfully isolated 28 bacterial strains with cellulose-degrading ability from soils collected in three representative wood-processing regions of Vietnam. Among these, five strains - Bacillus velezensis D183.1.B1, B. amyloliquefaciens D183.2.B3, B. cellulosilyticus D111.1.B1, Pseudomonas fluorescens D751.1.B2, and P. aeruginosa D111.3.B2 - exhibited the highest CMC-degrading activities and were selected for further studies.

Morphological, biochemical, and physiological characterizations revealed clear differences between Bacillus and Pseudomonas groups, while 16S rRNA gene sequencing confirmed their taxonomic identity with 97.8 - 100% similarity to known species. The selected strains showed distinct cellulase production profiles under varying pH, temperature, and incubation times. Optimal enzyme activity was achieved at pH 6–8, 35°C, and 48 - 60 hours, with Bacillus velezensis D183.1.B1 producing the highest cellulase activity (7.6 ± 0.2 U/mL at 60 h).

These findings demonstrate the diversity and potential of indigenous cellulolytic bacteria in Vietnam’s wood-processing environments. The isolates, particularly those belonging to the genus Bacillus, represent promising candidates for biotechnological applications such as the bioconversion of lignocellulosic biomass, enzyme production, and biological treatment of cellulose-rich industrial wastewater. Further optimization of fermentation parameters and gene-level analysis could enhance enzyme yield and stability for large-scale applications.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the project of Joint Vietnam - Russia Tropical Science and Technology Research Center with code SH.D1.05/23 for creating favorable conditions in terms of facilities and research support during the process of writing the article.

Statement on the use of Generative AI: The author(s) declare that AI tools were used only for language editing and formatting, and not for generating any scientific content. All data, analyses, and interpretations were conducted and verified by the authors, who take full responsibility for the manuscript.

Author contributions: Phung Duc Tan, Do Thi Thu Hong: Conceptualization; Phung Duc Tan, Nguyen Thi Kim Thanh: Methodology. Phan Thanh Xuan, Nguyen Thi Kim Thanh, Do Thi Thu Hong: Investigation; Phung Duc Tan, Phan Thanh Xuan Data curation; Phung Duc Tan, Phan Thanh Xuan: Formal analysis; Phung Duc Tan: Writing – original draft; Do Thi Thu Hong: Writing – review & editing; Do Thi Thu Hong Supervision; Phung Duc Tan, Nguyen Thi Kim Thanh: Visualization; Do Thi Thu Hong: Project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper. This study was not supported by external funding; it was conducted as part of internal research activities at the project of Joint Vietnam - Russia Tropical Science and Technology Research Center with code SH.D1.05/23.

Tài liệu tham khảo

2. T. Q. Tai, N. D. Khanh and Q. V. C. Thi, Characterization and identification of potential cellulolytic bacteria for bio-degradation of durian shell waste in Mekong Delta, Vietnam, Biodiversitas, Vol. 25, No. 11, pp. 4284-4291, 2024. DOI: 10.13057/biodiv/d251128

3. A. Cavka, X. Guo, S.J. Tang, S. Winestrand, L. J. Jönsson and F. Hong, Production of bacterial cellulose and enzyme from waste fiber sludge, Biotechnology for Biofuels, Vol. 6, No. 25, 2013. DOI:10.1186/1754-6834-6-25

4. R. Mahmood, N. Afrin., S. N. Jolly and R. Y. Shilpi, Isolation and identification of cellulose-degrading Bacteria from different types of samples, World Journal of Environmental Biosciences, Vol. 9, Issue 2, pp. 8-13, 2020.

5. R. Garcia, I. Calvez1, A. Koubaa, V. Landry, and A. Cloutier, Sustainability, circularity, and innovation in wood‑based panel manufacturing in the 2020s: Opportunities and challenges, Wood Structure And Function, Vol. 10, pp. 420-441, 2024. DOI: 10.1007/s40725-024-00229-1

6. D. T. T. Tam, T. T. Yen and N. T. Huyen, Characterization of potential cellulose-degrading Bacteria isolated from by-products of wood processing, Vietnam Journal of Agricultural Sciences Vol. 21, No. 8, pp. 1028-1036, 2023.

7. G. Chen, G. Wu, B. Alriksson, W. Wang, F. F. Hong and L. J. Jönsson, Bioconversion of Waste Fiber Sludge to BacterialNanocellulose and Use for Reinforcement of CTMPPaper Sheets, Polymers, Vol. 9, pp. 458-472, 2017. DOI: 10.3390/polym9090458

8. D. Kungulovski, N. Atanasova-Pancevska and E. D. Josifovska, Isolation, screening and characterization of cellulolytic bacteria from different soil samples from pelagonia region, Journal of agriculture and plant sciences, Vol. 21, No.1, 2023. DOI: 10.46763/JAPS23211061k

9. A. M. Sousa, I. Machado, A. Nicolau and M. O. Pereira, Improvements on colony morphology identification towards bacterial profiling, Journal of Microbiological Methods, Vol. 95, Issue 3, pp. 327-335, 2013. DOI: 10.1016/j.mimet.2013.09.020

10. N. N. An, N. M. Tan, N. T. T. Hien, N. T. D. Hanh and P. T. Viet, Isolation, selection and enhanced cellulase production of TH-VK22 and TH-VK24 bacterial strains, Journal of Science and Technology, Vol. 39B, pp. 247-259, 2019.

11. N. T. T. Nga, P. Q. Nam, L. X. Phuc, P. Q. Thu and N. M. Chi, Isolating and screening cellulolytic microorganisms to produce organic biofertilizer, Vietnam Journal of Science and Technology, Vol. 2, pp. 3841-3850, 2015.

12. C. Mawadza, R. Hatti-Kaul, R. Zvauya and B. Mattiasson, Purification and characterization of cellulases produced by two Bacillus strains, Journal of Biotechnology, Vol. 83, Issue 3, pp. 177-187, 2000. DOI: 10.1016/S0168-1656(00)00305-9

13. A.K. Ray, A. Bairagi, K. Sarkar Ghosh and S.K. Sen, Optimization of fermentation conditions for cellulase production by Bacillus subtilis CY5 and Bacillus circulans TP3 isolated from fish gut, Acta Ichthyologica et Piscatoria Vol. 37, No.1, pp. 47-53, 2007. DOI: 10.3750/AIP2007.37.1.07

14. D. Chettri, A, K. Verma, Statistical optimization of cellulase production from Bacillus sp. YE16 isolated from yak dung of the Sikkim Himalayas for its application in bioethanol production using pretreated sugarcane bagasse, Microbiological Research, Vol. 281, 2024. DOI: 10.1016/j.micres.2024.127623

15. G. Zhang, Y. Dong, Design and application of an efficient cellulose-degrading microbial consortium and carboxymethyl cellulase production optimization, Frontiers in Microbiology, Vol. 13, 2022. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2022.957444

16. M. N. Anahtar, B. A. Bowman and D. S. Kwon, Efficient nucleic acid extraction and 16S rRNA gene sequencing for Bacterial community characterization, Method Article, Vol. 110, 2016. DOI:10.3791/53939

17. https://bqlckcn.laocai.gov.vn/dac-diem-tinh-hinh-542a7fdf-b7f1-473f-b85b-76bb98cc2a6e/khi-hau-1537488 [Access Nov, 10, 2025]

18. R. Toczyłowska-Maminska, Wood-based panel industry wastewater meets microbial fuel cell technology, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Vol. 17, Issue 7, 2020. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph17072369

19. R. Datta, Enzymatic degradation of cellulose in soil: A review, Heliyon, Vol. 10, Issue 1, 2024. DOI: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24022

20. Anu, S. Kumar, A. Kumar, V. Kumar and B. Singh, Optimization of cellulase production by Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis JJBS300 and biocatalytic potential in saccharification of alkaline-pretreated rice straw, Preparative Biochemistry & Biotechnology, Vol. 51, No. 7, pp. 697-704, 2021. DOI: 10.1080/10826068.2020.1852419

21. I. K. Kiio1o, M. M. F. Jackim, W. B. Munyali and E. K. Muge, Isolation and characterization of a thermostable cellulase from Bacillus licheniformis strain vic isolated from Geothermal Wells in the Kenyan Rift Valley, The open biotechnology journal, 2016. DOI: 10.2174/1874070701610010198

22. S. Singh, V. S Moholkar and A. Goyal, Optimization of carboxymethylcellulase production from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SS35, 3 Biotech, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 411-424, 2013. DOI: 10.1007/s13205-013-0169-6

23. M. S. Demissie, N. H. Legesse and A. A. Tesema, Isolation and characterization of cellulase producing bacteria from forest, cow dung, Dashen brewery and agro-industrial waste, PLoS One, Vol. 19, No. 4, 2024. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0301607

24. F. Wahid et al., Bacterial cellulose and its potential for biomedical applications, Biotechnology Advances, Vol. 53, 107856, 2021. DOI: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2021.107856